On March 30, “No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man” opened at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, D.C. The free exhibition of installation art, jewelry, wearable art, interactive digital art, and photography threw open the doors to Burning Man’s maker ethos and delighted audiences from across the United States and around the world. Renwick curator Nora Atkinson and her team worked hard to activate the Burning Man approach to art within the limits of a museum’s four walls, and exhibition partners such as The Golden Triangle Business Improvement District provided public space near the Renwick for six large-scale sculptures.

On March 30, “No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man” opened at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, D.C. The free exhibition of installation art, jewelry, wearable art, interactive digital art, and photography threw open the doors to Burning Man’s maker ethos and delighted audiences from across the United States and around the world. Renwick curator Nora Atkinson and her team worked hard to activate the Burning Man approach to art within the limits of a museum’s four walls, and exhibition partners such as The Golden Triangle Business Improvement District provided public space near the Renwick for six large-scale sculptures.

Over 740,000 visitors, many of them children and young people, saw the exhibition before the end of 2018, giving a wide variety of people the chance to engage with our ethos and aesthetics — an opportunity many would not have had otherwise.

Over 740,000 visitors, many of them children and young people, saw the exhibition before the end of 2018, giving a wide variety of people the chance to engage with our ethos and aesthetics — an opportunity many would not have had otherwise.

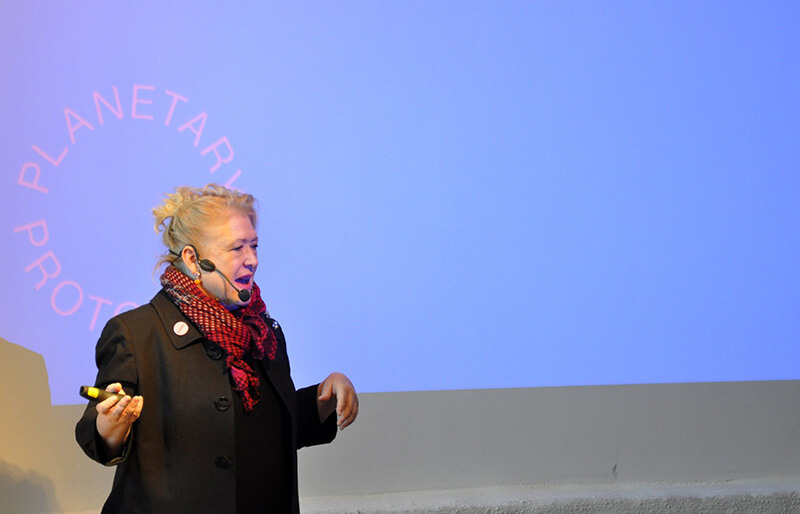

On September 14, a day-long storytelling symposium hosted by the Smithsonian American Art Museum celebrated Burning Man’s verbal and visual culture. Co-founders, artists, leaders, and local community members shared personal tales of change that emphasized the deep sense of connection and belonging they had gained through Burning Man, as well as the permission they felt to live life to their choosing. Many also shared how their sense of personal fulfillment sparked a powerful desire to give back through public service and supporting others.

On September 14, a day-long storytelling symposium hosted by the Smithsonian American Art Museum celebrated Burning Man’s verbal and visual culture. Co-founders, artists, leaders, and local community members shared personal tales of change that emphasized the deep sense of connection and belonging they had gained through Burning Man, as well as the permission they felt to live life to their choosing. Many also shared how their sense of personal fulfillment sparked a powerful desire to give back through public service and supporting others.

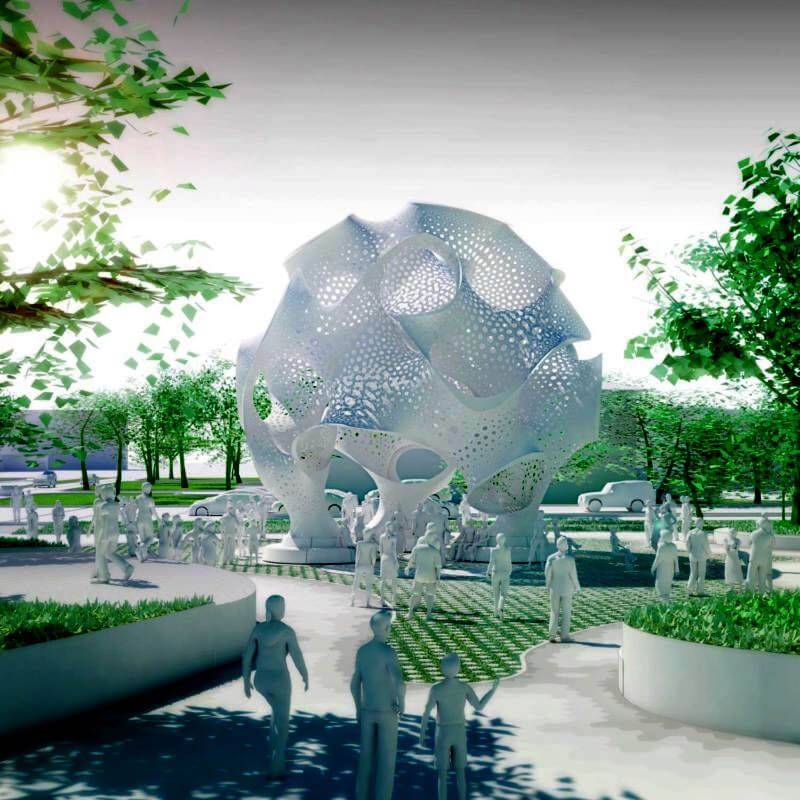

In March, we announced Burning Man Project was invited to facilitate the creation and installation of five artworks for a two-acre public plaza in Google’s new Charleston East Plaza Campus. The project aims to create a plaza that is inclusive, dynamic, interactive, fun, and memorable, offering delight, inspiring curiosity, and steering away from formal “don’t touch” experiences. The project will also create new opportunities for Burning Man artists to do their work in the world.

In addition to facilitating the selection of artworks, we’ve spent the past nine months undertaking highly participatory community engagement for the project. We’ve held public meetings to listen and learn about local aesthetic needs, and run two human-centered design workshops encouraging participant teams to consider: “How might we create a place where people gather, linger and feel ownership?”

In addition to facilitating the selection of artworks, we’ve spent the past nine months undertaking highly participatory community engagement for the project. We’ve held public meetings to listen and learn about local aesthetic needs, and run two human-centered design workshops encouraging participant teams to consider: “How might we create a place where people gather, linger and feel ownership?”

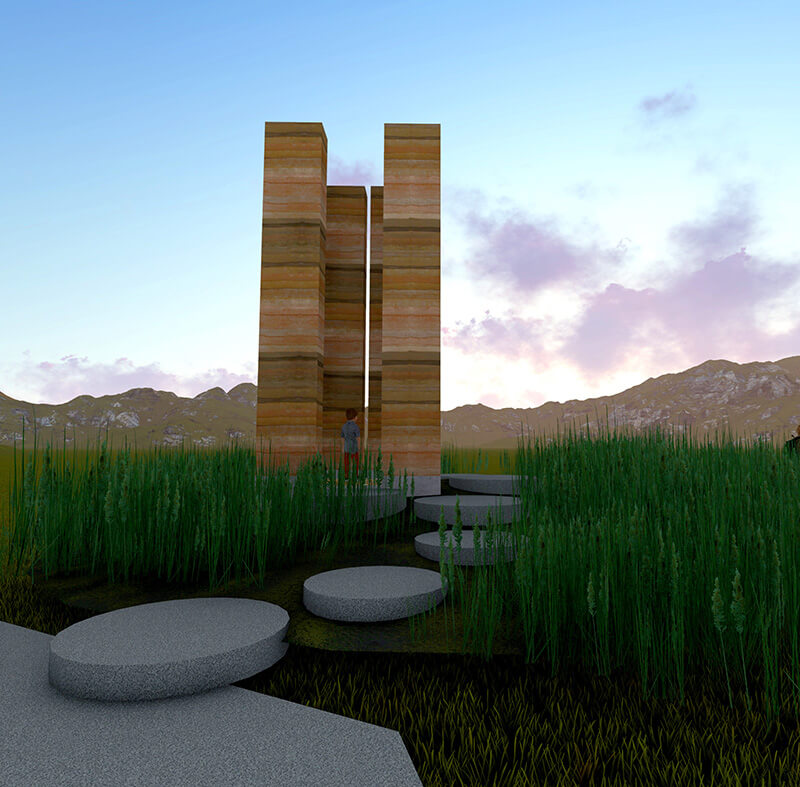

We also continued our work on Nevada’s Washoe County Art Trail project, a 200-mile interactive trail highlighting art, history, and culture of this part of Northern Nevada. In 2017, we put a call out for artists to create two installations for the trail, which evoked a sense of home. In 2018, we selected a collaboration between Reno artist Davey Hawkins and the “ROAM” group to install two rammed-earth sculptures at each end of the trail, one in Crystal Peak Park and the other in Gerlach.

We also continued our work on Nevada’s Washoe County Art Trail project, a 200-mile interactive trail highlighting art, history, and culture of this part of Northern Nevada. In 2017, we put a call out for artists to create two installations for the trail, which evoked a sense of home. In 2018, we selected a collaboration between Reno artist Davey Hawkins and the “ROAM” group to install two rammed-earth sculptures at each end of the trail, one in Crystal Peak Park and the other in Gerlach.

The project is about more than installing art; it’s also about making meaning and activating culture with project partners, stakeholders, and community members. Burning Man Project facilitated a series of community story circles in Reno, Sparks, Gerlach, Verdi, and Nixon. Miners, ranchers, and other community members in attendance had precious history to share. These stories will become part of an augmented-reality app that will enable people to connect with the 16 selected sites along the trail.

We also co-hosted a meeting with representatives from Gerlach, the Nevada Art Commission, the Paiute Tribe, the Nevada Museum of Art, and the Reno Arts Council, where we began the day by sharing an item and story that represented our connection to Washoe County. This helped turn the room into a “we,” rather than a presentation by “us” to “them.”

Working with Burning Man Project isn’t “business as usual,” and we’ve encouraged this year’s partners to do things differently as we seek to create environments that enhance common bonds and generate authentic human connections. As we move deeper into this partnership work, we continue to learn how to best influence institutions beyond our playa world.

Working with Burning Man Project isn’t “business as usual,” and we’ve encouraged this year’s partners to do things differently as we seek to create environments that enhance common bonds and generate authentic human connections. As we move deeper into this partnership work, we continue to learn how to best influence institutions beyond our playa world.